Setting up an Intel Edison

This is a guide to getting started with the Intel Edison.

Intel has published a guide for getting started with this device as well, but I wanted to get everything into one place, tell it from my perspective, and smooth over a couple of the bumps I hit on the way. Let me know with a comment below if you have any questions.

I like to keep things simple, so I’m going to help you get started with the Edison as easily as possible.

In a subsequent post, I’m going to show you how you can very, very easily start writing JavaScript to control your Edison. You won’t have to deal with Wiring code, you won’t have to install the Arduino IDE (argh!), and you won’t have to install Intel’s attempt at an IDE - Intel XDK IoT Edition. You’ll be able to use Visual Studio, deploy to the device wirelessly, and then have plenty of time when it’s done to jump in the air and click your heels together.

In another post, I’m going to show you how to use Azure’s Event Hub and Service Bus (via a framework called NitrogenJS) to not only do cool things on one Edison, but to do cool (likely cooler actually) things on multiple Edisons, other devices, webpages, computers, etc.

Introducing the Edison

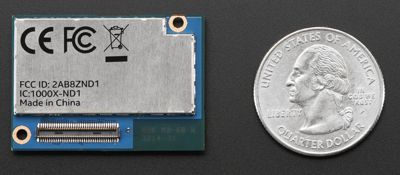

The Edison is tiny. It’s the size of an SD card. Despite its size, though it has built in WiFi and Bluetooth LE and enough processor and memory oomph to get the job done.

The design of the Edison is such that it’s pretty easy to implement a quasi-production solution. It’s not always easy getting a full Arduino board into your project, but the Edison is almost sure to fit.

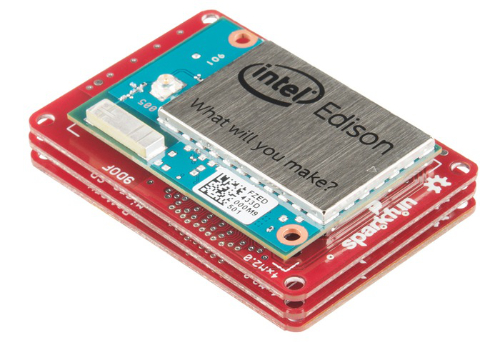

I’m not the only one that’s excited about this System on a Chip (SoC) either. Sparkfun.com is too. They made a great video introducing the technical specs of the Edison and showcasing their very cool line of modules that snap right on to the Edison’s body. Here you can see a few of those modules piled up to produce a very capable solution…

That’s the kind of compact solution I’m talking about. The only problem is that at the time of writing, the modules are only available for pre-order.

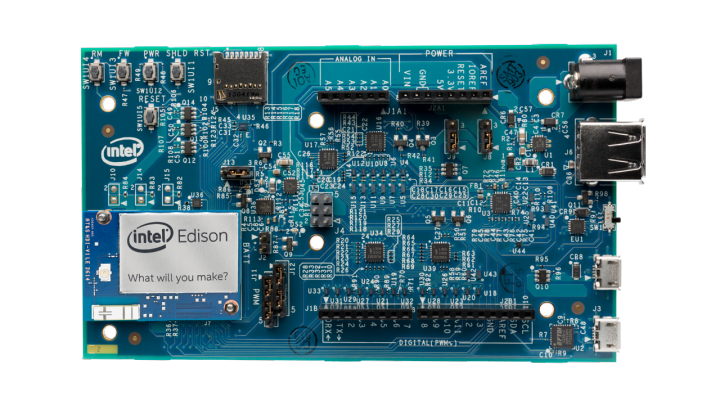

Not to worry though, there are a couple of other ways to interface with the Edison and get working on your project. The recommended way is by using the Arduino dev board. This is what the Edison looks like when it’s snapped to the dev board.

This dev board explodes all of the functionality packed into the Edison and makes life easy. It gives you USB headers, a power plug, GPIO (general purpose input/output) pins, a few buttons, and a micro-SD card slot.

There’s another dev board available for the Edison - a mini board - but it’s less used because it requires soldering and doesn’t offer as many breakouts. If you’re looking for compact, you can just wait for the Sparkfun modules I mentioned. Here’s the Edison mounted on its mini board…

In this guide, I’ll take you end to end with getting the Edison setup on a Windows machine. I am not prepared to detail instructions for Mac/Linux, but Intel did a good job of that on their guide anyway. I’m going to mention the physical setup of the device, installation of the drivers (on your host PC running Windows), then walk you through flashing it with Intel’s custom Yocto Linux image and training it to connect to Wifi. When we’re all said and done, we’ll never have to plug the Edison into our host PC via USB again. We’ll be able to wirelessly deploy software and otherwise communicate with the device. Finally, we’ll write a simple bit of code, but in a follow up post, we’ll get crazy with software, because that’s what we do.

Physical Setup

Physically setting up the Edison once you’ve pulled it out of the box is pretty straight forward. I’ll assume you’re starting with the Arduino dev board.

Add the plastic standoffs to the dev board if you’d like. They’re good for keeping Edison’s sensitive underbelly from touching anything conductive and creating a dreaded short.

Next snap the Edison chip onto the board. You can put the tiny nuts onto the posts to hold the chip on, but I choose to rely on the solid friction fit instead.

Flashing

Before your Edison is going to do anything exciting, you’ll need to connect to it and flash it with the latest version of the Yocto Linux distribution that is provided by Intel. At first, it has no idea how to connect to a Wifi hotspot, so we’ll have to establish a serial connection. It’s quite easy actually.

Intel’s guide does a decent job of walking you through these steps, but again, I’m going to do it on my own to add my own perspective and lessons learned.

The guide asks you to plug in both USB cables. That will work, but it helps to understand why. One of the USB micro plugs (the one closest to the power plug and the larger USB port) is a host plug that will a) power the Edison via USB and b) will cause a certain directory from its file system to appear in Windows Explorer as a drive. The other USB micro plug (the one closest to the edge of the board) is a serial connection that will allow you to establish a 115200 baud serial connection before Wifi is established.

What I prefer to do is power the Edison with a barrel connector, and then just use one USB cable plugged in to whichever header I need. This works well especially since one of them is only need for one step upon initial setup - to flash the device. I have a USB to barrel connector, so I can simply plug my Edison into a USB battery pack and emphasize that it’s completely wireless.

Do make sure the itty bitty switch next to the USB micro plugs is switched toward the USB micro plugs.

Download and install FTDI drivers. First, you need to download and install the FTDI drivers which allow your host computer to communicate with the USB header on the Edison. The file you download (“CDM…”) can be directly executed, but **I had to run it in compatibility mode **since I’m running Windows 10. I won’t insult your intelligence by telling you how to hit Next, Next, Finish.

Download Intel Edison Drivers. Now you need drivers for RNDIS, CDC, and DFU. It sounds hard, but it’s not. Go to Intel’s Edison software downloads page and look for the “Windows Driver setup”. This downloads a zip file called IntelEdisonDriverSetup1.0.0.exe. Execute the file and comlete installation. The download goofed up for me in IE11 on Windows 10, so if you run into that, go to the link at the bottom of the page that says it’s for “older versions”. The download for that same file is there and it’s not an older version.

Note: In case you want to know, the RNDIS (Remote Network Driver Interface Spec) is for virtual Ethernet link over USB, the CDC (Composite Device Class) is a standard for recognizing and communicating with devices, and DFU (Device Firmware Upgrade) is functionality for updating firmware on devices.

**Copy flash files over. **With these two driver packs installed, you should have a new Windows drive letter in Explorer called Edison. This is good, because that’s where you copy the files that will be used to flash the device. Go back to the Intel Edison software downloads page and locate and download “Edison Yocto complete image”. Save it local and unzip it. Now make sure the Edison drive in Windows Explorer is completely empty and then copy the entire contents of the zip file you just downloaded into that drive.

Connect to the device using serial. Since we’re finished copying files to the device and ready to connect to it over serial, we need to switch the USB cable from the inner port to the outer port. Do make sure you have the USB to barrel connector in place so you get the reassuring power light on the board.

The Intel guide walks you through using PuTTY (a Windows client for doing things like telnet, SSH, and serial connections). I’m a command line guy, so I use a slightly different approach using PowerShell which I’ll present. You can choose which you like better.

Go to the PuTTY download page, download plink and save the resulting plink.exe file into some local directory. I use c:\bin. Now you’re ready to use PowerShell to connect to a serial port. Very cool.

Note: plink in PowerShell does something goofy with the backspace key. It works, but it renders

?[Jfor each time it’s pressed. If you know a way around this, let me know.

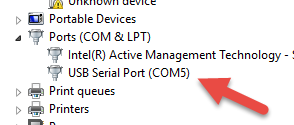

Before you connect, you have to see what the COM port is for the Edison. Go to Device Manager and expand the Ports (COM & LPT). Now look for USB Serial Port (COM_X_). Mine is COM5.

Here’s the line I use to connect (actually, I put a plink function in my $profile to make it even easier… ask me if you want to see how)…

. c:\bin\plink.exe -serial COM5 -sercfg 115200,8,1,n,Namely |

…if you saved your plink.exe into a different location or if your COM port is different then change accordingly.

Execute that line and then hit enter a couple of times. You should find yourself at a root@edison:~# prompt. That’s good news. Your on the device!

Initiate the flash. To flash your Edison using the files you copied into the drive, you simply type reboot ota and hit Enter. Watch your device do a whole bunch of stuff that you don’t have time to understand, and rejoice when it finishes and returns you to the login prompt. Your login is root and you don’t have a password. You should be sitting at root@edison:~# again.

Setup wireless. You have a full Linux distribution flashed to your Edison now, and it’s ready to talk Wifi. You just have to configure a couple things. Namely, you have to a) give your Edison a password (technically, provide a password for the root account), b) make sure your host PC is on the same network as your Edison, and c) provide your SSID and password. The first point is one thing the Intel guide skips - the need to set a password on the root account. If you don’t do it, you won’t be able to SSH to the device over Wifi. To initiate, execute configure_edison --setup. You’re prompted for a device name. I like to name mine (mine are called Eddie and Betty) so they’re easier to differentiate in terminal windows. I provide easy passwords for mine, because I’m not exactly worried about getting hacked. Next, you’ll be prompted to setup up Wifi. Follow along, choose the right hotspot, and enter the Wifi password when prompted.

Connect to the device using SSH over TCP/IP via the Wifi. Let’s get rid of this silly hard link and serial connection and join the modern era with a Wifi connection. Disconnect from the plink connection using CTRL+C. You can pull that USB cable out of your Edison’s dev board too. Your Edison is now untethered! Well, except for power, but a battery could take care of that.

Now again, I’ll diverge from the Intel guide here so I can stick with the command line. I use Cygwin on my box to allow me to SSH via PowerShell. I like it a lot. EDIT: Thanks to @palermo4 for pointing out that it’s not Cygwin that’s giving me this functionality, but rather my install of GitHub for Windows and the fact that I subsequently added GitHub’s bin folder to my path in Windows. Simply install GitHub for Windows and then go to your Environment Variables in Windows, edit the PATH variable, and append your bin directory to the end. On my system, it’s at C:\Users\jerfost\AppData\Local\GitHub\PortableGit_7eaa994416ae7b397b2628033ac45f8ff6ac2010\bin; I’m guessing yours is different :) After adding this, test it by typing SSH<Enter> in PowerShell and see if you get something besides an error.

You can use this approach, or you can go back to the Intel guide and use the PuTTY approach.

Before you can SSH to your device, you have to figure out what it got for an IP address. But the Edison has done something nice for you there. It created name.local as a DNS entry, so to connect to an Edison with the name eddie, you can simply use eddie.local. Mine is resolving to 192.168.1.9. If this doesn’t work for you, you can always log in to your router and find out what IP address was assigned to it or you can go back to the serial connection and type ifconfig at the prompt and look for the wlan0 network and see what address was assigned.

From my PowerShell prompt, I can just type ssh root@eddie.local. You’re connected to your Edison over Wifi now, and you’re so very happy!

Ready to Write Code!

From here, you’re ready to write some code. I’m going to write an extensive blog post on the topic, but for now, let’s get at least a taste.

First, make sure you’re SSH’ed to the device. So run that same ssh root@eddie.local command and sign in with your password.

Hello World! First things first. Let’s greet the world using JavaScript (via NodeJS). Type node and hit Enter and you should be at a > prompt. You’re in NodeJS… on your Edison. Man, that was easy.

Now type console.log('Hello World'); and hit Enter. There you have it.

Hit CTRL+C twice to get back to your Linux prompt.

Blink the light, already! You haven’t gotten started with an IoT device until you’ve blinked an LED, so let’s get to it. Still SSH’ed to your device, execute each of these lines (each at the prompt) followed by Enter…

node //enter NodeJS again |

And this is full-on JavaScript, so you can go crazy with it (recommended). Try this…

var state = 0; //create a variable for saving the state of the LED |

The light should be flashing on and off, but your state of bliss should be sustained high!

It’s obviously not sustainable to write our code at the prompt, so stay tuned for my next guide on writing code for your Edison.

Have fun!